Object-oriented Programming In Python

Object Oriented programming (OOP) is a programming paradigm that relies on the concept of classes and objects. It is used to structure a software program into simple, reusable pieces of code blueprints (usually called classes), which are used to create individual instances of objects.

Table of Contents

Overview of Classes and Objects

A class is an abstract blueprint used to create more specific, concrete objects. Classes often represent broad categories, like Car or Dog that share attributes. These classes define what attributes an instance of this type will have, like color, but not the value of those attributes for a specific object.

Classes can also contain functions, called methods, available only to objects of that type. These functions are defined within the class and perform some action helpful to that specific type of object.

Class templates are used as a blueprint to create individual objects. These represent specific examples of the abstract class, like myCar or goldenRetriever. Each object can have unique values to the properties defined in the class.

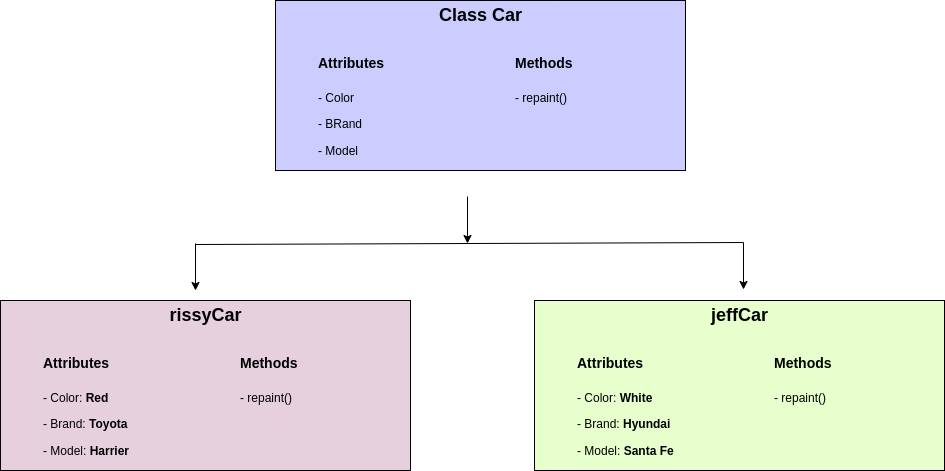

If we have a sample class called "Car" that contains all the properties a car must have such as color, brand and model, we can create an instance of a type of car to represent a specific car.

We can then set the value of the properties defined in the class to describe our car, whithout affecting other objects or the class template.

We can reuse this class to represent any number of cars.

Let us look at this example below:

The "Car" class has been used to create two car type objects, rissyCar and jeffCar. The class has provided abstract definition of what a car should have, and the objects provide the actual values specific to them.

Real-life Application of OOP

Imagine running an education center with hundreds of students. During registration, you will need to capture all necessary information about a particular student. How would you design a simple and reusable software to model the students?

It would be very inefficient to write unique code specific for each student as follows:

ambrose = { name: 'Ambrose', age: 10, course: 'Scratch', parent: 'Esther' } emilly = { name: 'Emilly', age: 13, course: 'Python', parent: 'Muthui' } kiki = { name: 'Kiki', age: 4, course: 'Scratch Jr', parent: 'Alfred' }

Above, you can see we have three objects, ambrose, emilly and kiki with duplicated code. Instead of repeating ourselves each time a new object is created, we can create a class that defines abstract information about a student, then instantiate an object of that class type.

class Student(): name = '<student name>' age = '<student age>' course = '<student course>' parent = '<parent name>' abrose = Student('Ambrose', 10, 'Scratch', 'Esther') emily = Student('Emilly', 13, 'Python', 'Muthui') kiki = Student('Kiki', 4, 'Scratch Jr', 'Alfred')

Building Blocks of OOP

There are four fundamental building blocks of object-oriented programming:

- Classes

- Objects

- Attributes

- Methods

Example

class User(): # Instance attributes def __init__(self, name, email): self.name = name self.email = email # Instance method def career(self, occupation): return f'{self.name} is a {occupation}' # Instantiate an object kiki = User('kiki', 'kiki@email.com') # Test the new object print('My name is ', kiki.name, ' and my email is ', kiki.email) # Call instance methods print(kiki.career('Teacher'))

| Classes | Objects | Attributes | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| As we have seen above, classes are essentially blueprints that define abstract ideas of an object. Individual objects are instantiated or created from this blueprint. | These are instances of a class, created with specific data. You can have multiple objects that use the same class. | These are the features of a class. They define the data that we would want an object to have. The state of an object is defined by the data in the object’s attributes fields. | Methods are used to represent behaviours. They perform actions that might return information about an object. When individual objects are instantiated, these objects can call the methods defined in the class. |

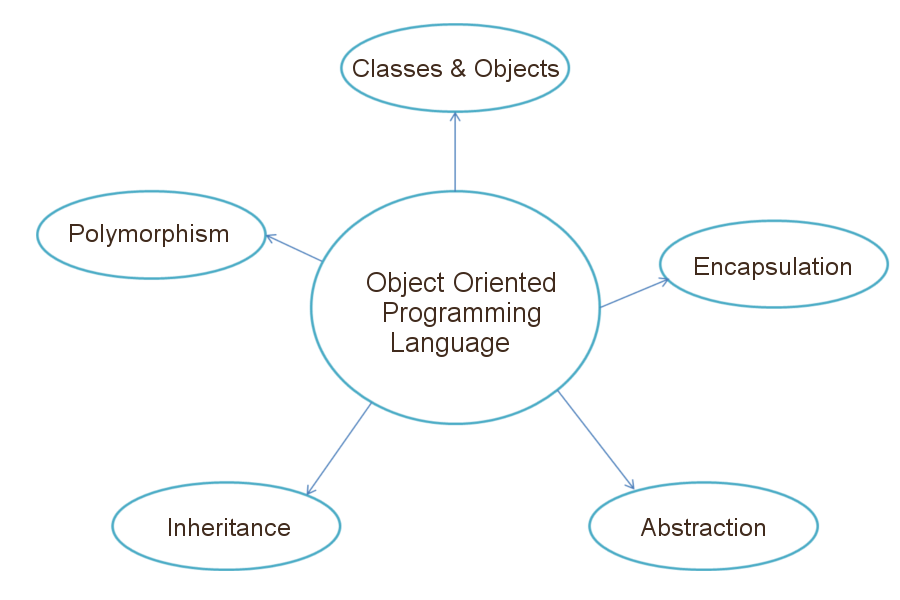

The Four Principles of Object-oriented Programming

The four pillars of OOP in python are:

Inheritance

This principle allows other classes to acquire the features of other classes. In other words, one class extends its attributes and behaviours to another class. The class in which the basic attributes and behaviours are defined is called the 'parent' class or the 'base' class. The class that inherits (or acquires) the attributes and behaviours of the parent class is called the 'child' class or the 'subclass'. The essence of inheritance is to promote code reusability.

class Parent(): def __init__(self, username, email): self.username = username self.email = email def __repr__(self): return f'Parent: {self.username}' class Child(Parent): pass

We have defined two classes: Parent and Child. The Parent class has the attributes username and email. This class is passed as a parameter in the Child class which, at the moment, has no attributes. To test how inheritance works, run the following in an active Python interpreter:

$ python3 >>> parent = Parent('harry', 'harry@email.com') >>> parent # Output Parent: harry >>> parent.username, parent.email # Output ('harry', 'harry@email.com') >>> child = Child('muthoni', 'muthoni@email.com') >>> child # Output Parent: muthoni >>> child.username # Output 'muthoni'

parent and child are objects of their respective classes. Instantiating these objects give data relevant to them. Notice that when you call the child object the output is "Parent: muthoni". This is because the child has inherited the in-built __repr__() function from the parent which has the string "Parent".

Polymorphism

Polymorphism is the ability to take many(poly) forms(morphism). Polymorphism in Python allows us to define methods that do not exist in the parent class or modify these methods if they exist in the parent class.

class Parent(): def __init__(self, username, email): self.username = username self.email = email def __repr__(self): return f'Parent: {self.username}' class Child(Parent): def __init__(self, username, email, age): super().__init__(username, email) self.age = age def __repr__(self): return f'Child: {self.username}, {self.age}''

We have modified the __repr__() function for the Child class to have its own string besides the dynamic username and email values. The Child class has an additional age attribute that does not exist in the parent. Let us see how polymorphism works.

$ python >>> parent = Parent('harry', 'harry@email.com') # Output Parent: harry >>> child = Child('muthoni', 'muthoni@email.com', 3) # Output Child: muthoni, 3

Notice that the parent's __repr__() function has been overriden by the child's. This is because the child defined its own __repr__() function. Additionally, the age attribute is only present in the child class.

Encapsulation

This principle promotes the need to hide data. From the word 'encapsulate', we learn that it means to 'enclose something in or as if in a capsule'. Synonyms associated with encapsulate are enclose, encase, confine, envelop etc. I hope you get the idea.

The creation of classes is by default encapsulation. This is because we are limiting access to the data from the outside world. This data can only be accessed using the said class. The entire process of encapsulation is also called 'information hiding'.

class Parent(): def __init__(self, username, email): self.username = username self.email = email def __repr__(self): return f'Parent: {self.username}'

In order for us to access any information about a parent, we will have to use the Parent class. We will instantiate an object, then use it to access whatever data we want.

Besides restricting access to the class data, we can more specifically limit access to individual variables and methods to prevent accidental data modification. Whenever we are working with the class and dealing with sensitive data, providing access to all variables used within the class is not a good choice.

class Parent(): def __init__(self, username, email, phone, salary): self.username = username self.email = email self.phone = _phone # < ----------- single preceding underscore self.salary = __salary # < ------------- double preceding underscores def __repr__(self): return f'Parent: {self.username}'

Encapsulation offers a way for us to access the required variable(s) without providing the program full-fledged access to all variables of a class. This mechanism is used to protect the data of an object from other objects.

Public members: The variables

usernameandemailare public members because they can be easily accessed within and outside theParentclass.class Parent(): def __init__(self, username, email): self.username = username self.email = email def __repr__(self): return f'Parent: {self.username}' # On an active Python interpreter $ python3 >>> parent = Parent('harry', 'harry@email.com') Parent: harry >>> parent.username harry

-

Protected members: The variable

phoneis a protected member and can only be accessed within the class and its subclasses. We know it is a protected member because it begins with a single underscore.

class Parent(): def __init__(self, username, email, phone): self.username = username self.email = email self._phone = phone # < ------------ protected variable def __repr__(self): return f'Parent: {self.username}' class Child(Parent): def __init__(self, username, email, phone, age): super().__init__(username, email, phone) self._age = age # < ------------ protected variable # On an active Python interpreter $ python3 >>> child = Child('rahima', 'rahima@email.com', 123, 12) >>> child._phone 123

Private member: The variable salary is said to be private and can only be accessed within the class. It has two preceding underscores.

class Parent(): def __init__(self, username, email, salary): self.username = username self.email = email self.__salary = salary def __repr__(self): return f'Parent: {self.username}, {self.email}, {self.__salary}' # On an active Python interpreter $ python3 >>> parent = Parent('harry', 'harry@email.com', 123) >>> parent Parent: harry, harry@email.com, 123 >>> parent.email harry@email.com >>> parent.__salary Traceback (most recent call last): File "oop.py", line 19, in <module> print(parent.__salary) AttributeError: 'Parent' object has no attribute '__salary'

Notice that we can easily access the public members of the Parent class. But the private member __salary (with double preceding underscores), we get the error AttributeError: 'Parent' object has no attribute '__salary'. This is so despite knowing that this variable can be accessed only within the Parent class.

Accessing Private Variables

How can we access a private variable? We will look at three ways:

Using public methods

Here, we can define an instance method which will have access to the private variable. Remember, we said that a private variable can only be accessed within its own class.

class Parent(): def __init__(self, username, email, phone): self.username = username self.email = email self.__phone = phone def __repr__(self): return f'Parent: {self.username}, {self.email}, {self.__phone}' def show_phone(self): print(f'Parent phone number is ', self.__phone) # On an active Python interpreter $ python3 >>> parent = Parent('harry', 'harry@email.com', 123) >>> parent.show_phone() Parent phone number is 123

The method show_phone() in an instance method of the Parent class. In it, we pass the private variable __phone.

Name mangling

To 'mangle' means to destroy or to severely damage by tearing or crushing. Other words used to mean mangle include mutilate, crush, disfigure etc. In OOP, name mangling is used to cleverly overcome the restriction of encapsulation.

class Parent(): def __init__(self, username, email, phone): self.username = username self.email = email self.__phone = phone def __repr__(self): return f'Parent: {self.username}, {self.email}, {self.__phone}' # On an active Python interpreter $ python3 >>> parent = Parent('harry', 'harry@email.com', 123) >>> parent Parent: harry, harry@email.com, 123 >>> parent.email harry@email.com >>> parent._Parent_phone 123

Typically, name mangling involves adding a preceding underscore to a class name then appending the double underscore private variable to it in order to gain access the variable's data. The format used is:

object._classname__privateVariable

Above, we have run parent._Parent__phone to gain access to a parent's private phone number.

Getter and setter methods

Proper encapsulation in python is normally implemented using getters and setters. Getter methods access data while setter methods are used to modify the data in private members.

class Parent(): def __init__(self, username, email, phone): self.username = username self.email = email self.get_phone = phone def __repr__(self): return f'Parent: {self.username}, {self.email}, {self.get_phone}' @property def get_phone(self): return self.__get_phone @get_phone.setter def get_phone(self, phone): self.__get_phone = phone # On an active Python interpreter $ python3 >>> parent = Parent('harry', 'harry@email.com', 123) >>> parent.get_phone 123 # New phone value >>> parent.get_phone = 100 >>> parent Parent: harry, harry@email.com, 100

Getter Method

When defining the Parent class, we add two special methods, both of which have similar names. The first method has a decorator called @property. Whenever this decorator is used, we know that it is an accessor or a getter method. It is used to access the value of the private variable phone.

@property def get_phone(self): return self.__get_phone

You might be wondering how phone has become private yet when defining the class attributes, we defined it as public (without underscores). Well, intentionally, when you want to encapsulate data using getter and setter methods, it is recommended that you pass class attributes as public members. Within the getter method (in our case it is the method get_phone), the returned value has two leading underscores. This makes it private.

It is important to note that the value

get_phoneamong the class attributes is not an assignment operation (self.get_phone = phone). Rather, we are calling our getter method so that it makes thephonevariable private.

Setter Method

Now that phone is private by the help of our getter method, we can focus on setting its value. A setter method uses a decorator whose name is similar to the getter method, then append the word setter. The method name is also similar to the getter method.

@get_phone.setter def get_phone(self, phone): self.__get_phone = phone

Again, the naming of the setter method is similar to that of the getter method. We know that it is a setter method because (1) it has the setter decorator, (2) we are assigning phone to __get_phone, our getter method. This method takes additional argurments compared to that of the getter method.

In an active Python interpreter, you will notice that the value of phone can only be accessed using the getter method which has been set using the setter method. It is only possible to alter the value of phone using the get_phone setter method.

Deleter Method

It is also possible to delete the value of a private member. All that needs to be done is to define a deleter method.

@get_phone.deleter def get_phone(self): del self.__get_phone # In an active Python interpreter $ python3 >>> del parent.get_phone >>> parent AttributeError: 'Parent' object has no attribute '_Parent__get_phone'

The deletion format is del object.deleterMethod.

Abstraction

Abstraction is used to hide the internal functionality of a process from the users. The users only interact with the basic implementation of the function, but inner working is hidden. For example, we mostly know that to increase the volume of a TV using a remote control, all we need to do is press the "+" button and the volume will go up. We do not know HOW the volume goes up, because that process has been hidden from us.

In Python, an abstract class can be considered as a blueprint for other classes. It allows one to create a set of methods that MUST be created within any child classes built from the abstract class.

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod class Parent(ABC): @abstractmethod def about_me(self): print('I am Harry') class Child(Parent): def about_me(self): print('I am Muthoni') # In an active Python interpreter $ python3 >>> child = Child() >>> child.about_me() I am Muthoni

We begin by first importing the ABC from the Abstract Base Class (ABC) because Python does not provide abstract classes. ABC works by decorating methods of the base class as abstract. A method becomes abstract when decorated with the keyword @abstractmethod. This method MUST then be used by all child classes.

In our example above, the Parent class defines an abstract method called about_me with its own custom print() statement. The Child class inherits the Parent class and overrides the print() statement with its own. If the child class tries not to use the defined abstract method, then an error is raised.

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod class Parent(ABC): @abstractmethod def about_me(self): pass class Child(Parent): def something_else(self): print('I am Muthoni Gitau') # In an active Python interpreter $ python3 >>> child = Child() >>> child.something_else() TypeError: Can't instantiate abstract class Child with abstract methods about_me

The Child class is required to have its own implememtation of the abstract method.

Share

If you enjoyed this article, you can share it with another person.

TweetNewsletter Subcription

Level up your skills.

We take your privacy seriously. Read our privacy policy. Unsubscribe | Resubscribe.